Hitler, Ataturk, and German-Turkish Relations

Posted By Edward Kanterian

An Interview with Stefan Ihrig

Special for the Armenian Weekly

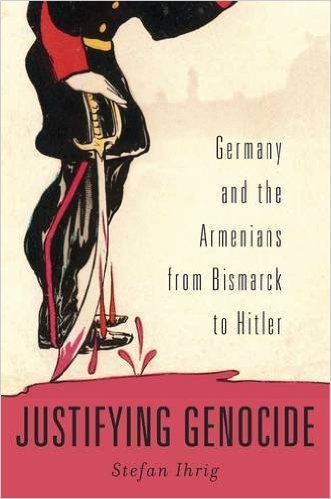

The following interview with Stefan Ihrig, author of Justifying Genocide: Germany and the Armenians from Bismarck to Hitler (due

out in December 2015), was conducted by Edward Kanterian, Senior

Lecturer in Philosophy at the University of Kent. Ihrig is the Polonsky Fellow at the Van Leer Jerusalem Institute.

***

Edward Kanterian—Mr.

Ihrig, we know that Mussolini was a major role model for Hitler. But it

is much less known that Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the modern

Turkish Republic, was another major source of inspiration for Hitler.

You have recently published a book exploring this. Why was Hitler

interested in Atatürk?

Stefan Ihrig—It

all goes back to the early 1920’s. Germany was still in shock about

losing the war and afraid of a punitive peace treaty imposed by the

Entente. In a mood of nationalist depression, events began to unfold in

Anatolia that stirred the passion and dreams of German nationalists.

Under Mustafa Kemal [Atatürk] the Turks were resisting their own

“Turkish Versailles”—the Treaty of Sèvres. They took on all of the

Entente as well as the Greek Army and even defied their own government

in Constantinople. What was happening in Anatolia was like a nationalist

dream-come-true for many in Germany. German nationalists, and the Nazis

especially, thought that Germany should copy what the Kemalists were

doing. Hitler was very much inspired by Atatürk and the idea of the

“Ankara government” in his attempt to set up an alternative government

in Munich in his Beerhall Putsch of 1923. Retrospectively, in 1933, he

called Atatürk and the Kemalists his “shining star” in the darkness of

the 1920’s. The Nazis and Hitler, in a political sense, had grown up

with Turkey and Atatürk. It was a fascination that would not go away and

transformed into something of a cult in the Third Reich.

E.K. —So the main attraction was the fact that Atatürk had resisted the Entente?

S.I. —Yes,

resisting the Entente and revising a Paris peace treaty fascinated the

Nazis. But this was not all. There was also the fact that Turkey had

“rid itself” of most of its minorities, first of the Armenians during

World War I, and second of most of the Greeks in the Treaty of Lausanne

population exchange. And finally, for the Nazis, what was happening in

Turkey in the 1920’s and 1930’s was a successful restructuring and

reconstruction of the country along nationalist/racial lines. For them

it was an example of what a purely national state could achieve under a

strong leader.

E.K. —The

Turkey which had “rid itself” of the Armenians was of course the Turkey

of the Young Turks, whose regime ended in 1918 and in which Atatürk

played only a minor role. So the Nazis’ fascination also extended to the

Young Turks? Presumably they were attracted by both the Young Turks’

and Atatürk’s Turkocentric conception of the Turkish state, which

excluded the multiethnic society that had existed hitherto in the

Ottoman Empire? Is there any direct link between the demographic and

exclusionary policies of Atatürk and that of the Nazis?

S.I. —The

Young Turks were not very important for the Nazis. But “ethnic

cleansing” and the Armenian Genocide before the War of Independence was,

for the Nazis, a major precondition for the success of Ataturk in that

war. And the expulsion of the Greeks was a second precondition, in the

Nazi view, for the further success of rebuilding Turkey along national

lines. Both were for the Nazis something of a “package deal.” What was

important for them was that the ethnic minorities—which they and other

German nationalists perceived to be like “the Jews”—were gone. In the

Nazis’ view of the New Turkey, all this would not have been possible had

Turkey not “rid itself” of the minorities. In this fashion, the Nazis

and other German nationalists were able to portray Atatürk’s New Turkey

as something of a test case of large-scale ethnic-racial

reconstruction—a test case that for them signalled the power of such a

new national state purged of minorities; a test case that not only

re-affirmed their own beliefs in the power of ethnically cleansed states

but showed various ways of how to achieve this.

E.K. —To

what extent was the Kemalist state ideology an inspiration to the

Nazis? Presumably they ignored the fact that Atatürk aimed to build a

republic in which the parliament, representing the people, was the main

source of power?

S.I. —The

Nazi vision of Atatürk’s New Turkey was a highly selective one. Almost

everything that conflicted with Nazi ideals and goals was either

downplayed or ignored. The emancipation of women was one such topic; it

was mentioned in passing but not deemed more noteworthy. Atatürk’s

rather peaceful foreign policy was purposefully misunderstood. When it

comes to the state of government under Atatürk, the Nazis saw a powerful

leader governing through a one-party system, which for them was the

only viable alternative to what they perceived as decadent Western

democracy.

E.K. —What was the Nazis’ attitude towards the “Armenian Question” in Turkey?

S.I. —In

the Nazi discussion of the Turkish War of Independence the Armenians

did not play a major role. Again, the Nazis had their own vision of

Atatürk’s rule and times. What was paramount for them was post-1923

Turkey, which they portrayed as something of a mono-ethnic paradise.

They simply refused to see any remaining minorities, such as the Kurds,

for example, and the conflicts that still existed within the Turkish

state. What made the Armenians, on the other hand, so important for the

Nazi discourse on Atatürk’s New Turkey was the specific German tradition

of seeing them as “the Jews of the Orient.”

E.K. —Can

you give some examples how Armenians were seen as “the Jews of the

Orient” in the German discourse? Was this something that happened only

after the First World War or even before?

S.I. —This German tradition has its beginnings in the late 19th century.

Around the same time as modern racial anti-Semitism gained ground, a

perception of the Armenians as racially similar or equivalent to the

Jews of Central Europe as portrayed in anti-Semitic discourse was put

forward. The Armenians were typically described as exploitative

merchants praying upon the kind and hard-working Turkish population.

This perception mainly focused upon the perceived parasitic,

treacherous, and non-productive behavior of the Armenians. That

Armenians carried out all kinds of crafts and labor—that many were, for

example, farmers—was simply ignored in these discourses. In the growing

racial and racialist literature from the late-19th century

up until the 1930’s, the Armenians were portrayed as a parent or sister

race of the Jews. Often they were even described as “worse than the

Jews.” This of course provides for a special German background to the

perception of the events of 1915/16 that is particularly chilling in

light of the further trajectory of German history.

E.K. —This brings us to your new book, which you have just completed, Justifying Genocide, which will be published by Harvard University Press later this year. How did you come to write this book?

S.I. —When

carrying out my research on the Nazis and Turkey, I came across a large

debate about the Armenian Genocide. This debate took place in the early

1920’s and is totally forgotten today. Yet, it was one of the largest

genocide debates of the 20th century.

It truly was a “genocide” debate, even before Raphael Lemkin coined the

term, because it was all about intent and extent of the “annihilation

of a nation.” I tried to reconstruct this debate and to find out why it

lasted so long. You have to envisage a four-and-a-half years long debate

including the first post-war discussions about what had happened, the

heated reception of the publication of Foreign Office documents on the

Armenian Genocide in 1919 already, a strong back and forth between those

condemning what happened as a “murder of a nation” and others denying

this. Furthermore there were assassinations, first of Talat Pasha in

1921 and then of another two prominent Young Turks in 1922, all of which

took place in Berlin and were much discussed in the press of the time.

I wanted to see where all the discursive building blocks employed in

these discussions came from, and thus I explored the German relationship

with the Ottoman Armenians since the late 1870’s. As it turns out,

since Bismarck’s time already the Armenians were assigned a very cynical

role in German foreign policy: They were regularly sold out in order

for Germany to gain political advantages and a more favorable position

in the Ottoman Empire. This continuous selling out of another Christian

people led to German discourses justifying mass murder already in the

1890’s, culminating in the propaganda during World War I as well as with

shocking justificationalist essays during the debate of the early

1920’s.

E.K. —Hitler’s

rhetorical question “Who, after all, speaks today of the annihilation

of the Armenians?” made in August 1939, apropos the war of annihilation

which he was about to start in the east, is well known. This suggests

that Hitler was at least inspired by the Armenian Genocide. In your new

book, you aim to demonstrate that the Holocaust and the Armenian

Genocide were indeed much more connected than previously thought. How

exactly?

S.I. —The

ongoing debate about recognition and denial has held the Armenian

Genocide in a hostage situation for almost a century and has also led to

it being often only a marginal footnote of broader European and world

history in our accounts and analyses of the time. Yet, it was immensely

important at the time, also and perhaps especially so in Germany. Not

only was Germany closely connected to it as a state and an ally of the

Ottomans, but so were many of its people as diplomats, officers, and

soldiers. The fact that the Ottoman Empire had garnered so much

attention in the German public and political sphere already before 1915

also connected Germany to the Armenian Genocide more closely. And

finally, the great German genocide debate of the early 1920’s brings the

whole matter within a mere decade of Hitler’s ascension to power. The

Armenian Genocide was both chronologically and geographically speaking

much closer to Germany and the Third Reich than is usually alleged; my

book illustrates this in many facets.

‘As it turns out, since Bismarck’s time already the Armenians were assigned a very cynical role in German foreign policy: They were regularly sold out in order for Germany to gain political advantages and a more favorable position in the Ottoman Empire. This continuous selling out of another Christian people led to German discourses justifying mass murder already in the 1890’s, culminating in the propaganda during World War I as well as with shocking justificationalist essays during the debate of the early 1920’s.’

E.K. —There are not many German historians who have researched the Armenian Genocide. What might be the reasons for this?

S.I. —The

topic continues to be one riddled with difficulties and potential

dangers. If you are a historian working on Turkish and Ottoman history,

you did not want to offend the very people you needed in order to get

access to your sources. Another reason was that many of the German

sources from the military archives were lost during World War II. Then

there was the suspicion that broader discussions of the Armenian

Genocide and its relation to Germany could be used to relativize the

Shoah. And finally, the official Turkish denialist campaign has conveyed

the lasting impression or rather has sown the confusion suggesting that

the topic is just too difficult and unapproachable. However, in recent

years many have worked on the German side, providing new studies on

particular aspects and also providing new narratives. I am sure we will

reach a critical mass in the field soon which will lead to a broader

re-evaluation of the Armenian Genocide within German, European, and

world history.

Αφιεώνεται στον Φίλη και τους λοιπούς κεμαλιστές της Αθήνας: O Χίτλερ, ο Κεμάλ και οι γερμανοτουρκικές σχέσεις

Αφιεώνεται στον Φίλη και τους λοιπούς κεμαλιστές της Αθήνας: O Χίτλερ, ο Κεμάλ και οι γερμανοτουρκικές σχέσεις